It may be easy to decide to let others pay for your union benefits, but to be an person of integrity, you’d have to believe you’d be better off without a union. Otherwise, you really would be just a freeloader.

But what’s it really like to work without a union? Many would brag that they could take care of themselves, that they don’t need anyone backing them up, but is this how it really works out?

Would You Make as Much Without a Union? Check the Facts

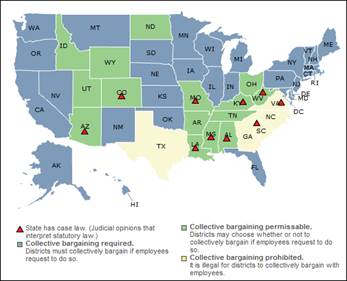

Michigan became a Right to Work state in 2012. Wisconsin banned teacher bargaining the previous year and just adopted its own Right to Work law. What’s it like to teach in Texas, where collective bargaining has been prohibited by law for many years? It turns out having a union to bargain for you makes a very big difference, including how much you make.

Bargaining is outlawed in just 5 states (Texas, Georgia, North and South Carolina and Virginia), but is ‘permissive’ in many more. That means management can bargain if it wants to. Imagine how that turns out. To make that decision easier, most of those states also restrict bargaining in various ways.

Some of these states have also imposed Right to Work laws, some haven’t. The result is a complicated and uneven environment in which unions represent their members.

But what’s the effect on teacher wages?

Higher teacher salaries are much more common in states that don’t suppress union strength. Other factors, no doubt, impact these salaries, cost of living, for one and how long these various laws have been in effect, for another. But the advantage of advocating together for better pay is pretty clear.

But after all, that’s just common sense.

Without a Union Behind You, You’re On Your Own

Detroit’s Pershing High School is part of Governor Snyder’s Education Achievement Authority, and is therefore non-union. A recent classroom fight at Pershing showed that teachers are literally on their own when it comes to controlling school violence.

When the two boys broke into a very violent fight, the teacher had few options. Having no working phones to contact security, she had been given a non-working walkie-talkie, so was left with the only resource she could find to break up an escalating and already violent fight: a broom.

Thanks to her inability to impact teaching conditions, she was forced to break up the fight with a broom and since been fired. Because the parents are now complaining about child abuse, school officials state that she may be charged with a crime.

Had she been represented by a union, her teaching conditions – no phone, a broken walkie-talkie, teaching alone in a school with a history of gang activity – would have been addressed. And because she’s since been fired and may be facing criminal charges, she would have a strong voice at her side, the protections provided in a contract as well as legal representation.

From begging to bargaining…a real life story

Bobby Crim came to Flint, Michigan in 1953 fresh out of the US Navy. He quickly found a job in the Buick plant which provided his family with good wages and benefits. As a member of the United Auto Workers, he learned how those wages and benefits came to be: collective bargaining.

In the 1930’s, the UAW organized auto plants in Flint and Detroit which spread to other plants and industries across the country. After a long battle to win bargaining rights, auto employees in the mid ‘50’s were the beneficiaries of that struggle some 20 years earlier. Bobby could have stayed in the plant and secured a comfortable future for his family—a future with financial security that the union and collective bargaining guaranteed.

But his dream was to become a teacher. Going to school at night on the G.I bill, he realized that dream and by the late 1950’s was teaching government in the Flint Public Schools. His dream did not come without a cost. The collective bargaining rights he enjoyed as an autoworker did not exist for public school employees—nor did the good wages, benefits and pensions. Taking a significant pay cut, he taught during the day and worked nights. Some nights he worked in the Flint post office—another job with union representation and collective bargaining. Some nights he tended bar. On good nights, he earned more tending bar than he did in his teaching job.

He moved his family to Davison, a suburb just east of Flint and took a job teaching in the Davison schools. At the same time, he began tending bar in Davison at night to continue supplementing his meager teaching salary. However, a few weeks later, he received a letter from the school board threatened to fire him if he continuing working at the bar in Davison. The school board felt it was inappropriate for a teacher to work as a bartender in town. He began to understand that unlike UAW members, school employees had no rights—they were “at will” employees who could be terminated without cause.

Sitting in the teacher’s lounge one day, he asked about “bargaining” for a new contract. A few teachers around the table laughed and said “Yes, that’s a good idea, Bobby. We nominate you to “bargain” our new “contract.” With that, they sent him to the Superintendent’s office (who happened to be the chairman of the local MEA group) with a “proposal.” The teachers of Davison would like a $100/year raise for the next school year. Of course, this was not the collective bargaining process he learned about in the auto plants. This was collective begging. If the Superintendent agreed to the teacher’s request, the “chief negotiator” would go back to the teacher’s lounge, tell colleagues the good news and they would go back to the classroom and happily continue teaching. If the Superintendent rejected the request, the “negotiator” slowly walk back to the teacher’s lounge, tell colleagues the bad news and they would go back to the classroom and teach their students.

That was the state of management/labor relations in public schools in the early 1960’s.

In 1964, Bobby took a big chance. He left his teaching job and entered a crowed primary field and became a candidate for the state legislature. Winning the democratic primary, he then won the general election in a Republican leaning seat (aided by the “Johnson landslide” of ’64). Bobby knew what his first priority was upon entering the legislature. What he didn’t know was this: 17 other school teachers were elected to the state house in 1964—all sharing the same goal: a law providing collective bargaining rights for school employees. Together, they achieved that goal, winning passage in both the house and senate and approval from Republican Governor, George Romney. The Public Employee Rights Act of 1965 was a dream come true for school employees. Some thirty years after auto workers gained union recognition and collective bargaining rights, school employees in Michigan won that same victory.

“Collective Begging” in Michigan Before Bargaining Was Legal

Judith Rood graduated from Wayne State University in 1951 and was soon hired to teach kindergarten in the Detroit Public Schools, 14 years before teachers were empowered to bargain by the Michigan Public Employees Relations Act (PERA).

Before bargaining was legal, there were no collective bargaining agreements. Each school employee was hired at a rate determined by the Superintendent and became an at-will employee. Collective action, even informal, was not allowed: “None of us were to compare salaries,” Rood said.

“My salary was lower than any male teacher. Elementary school teachers all earned less than high school teachers. Single men earned less than married men. When I announced that I was pregnant, I was told that I must take a two year leave of absence, without pay, as soon as I wore maternity clothes or at six months of pregnancy.”

The situation was the same in northern Michigan. In Marquette, pregnant teachers were required to leave at five months and care for their newborn for a year. They were not guaranteed a job at the end of that year. In the Alpena schools, husbands and wives couldn’t work in the same building.

Other aspects of their private lives were also not out of bounds. Marquette teacher Tom Baldini remembers that although personal leaves were allowed (just two per year), “The administration wanted to know why you were asking for a personal day. Teachers were called into the principal’s office, if not the superintendent’s, about being seen in a local bar.”

Other aspects of their private lives were also not out of bounds. Marquette teacher Tom Baldini remembers that although personal leaves were allowed (just two per year), “The administration wanted to know why you were asking for a personal day. Teachers were called into the principal’s office, if not the superintendent’s, about being seen in a local bar.”

Before bargaining was legal, teachers also had no input into how their schools were run. Judy Foster taught in Dearborn Heights in 1964. “My study hall had 100 kids and there were around 40 students in nearly every class. There was no limit.”

Foster also worked in the Blissfield schools. As a Home Economics teacher, she was expected to cater all school functions. “I also had to find students to do the serving. Neither they nor I got paid; I was told it was part of the job. I had no choice.”

In 1961, Roy Kemppainen taught in Merrill, Michigan. “I earned $4,400 in my first year. We were promised a $200 increase in the second year but some water pipes froze, so the teachers only received a $100 increase.” In 1962, during good financial times, the raise for an Alpena teacher with a Bachelor’s Degree was $39.

Salaries were imposed by the administration. “In the early years, there was no salary schedule so teachers were paid whatever the school district wanted to pay, with some teachers being paid considerably more or less than others. Teachers could take it or leave it with very little input,” Kemppainen said.

Before bargaining was legal, teacher unions were largely limited to “teacher clubs”, which included the principals and superintendents. George Worden was a member in Reese, Michigan. “Topics at the monthly Reese Teachers Club meeting dealt with stuff other than salary. The Superintendent occasionally gave a report about the latest changes in school law.”

These teacher clubs were affiliated with the MEA, which trained local salary committees on negotiation skills. Worden was on one such committee. “I was asked to attend a Salary Workshop in October 1964.The training session was conducted by Tom Northey, MEA’s research specialist. He introduced me to school finance including the Form B, which each public school submitted to the state at the end of its fiscal year.”

“Northey also told us that we deserved a whole lot more salary and he encouraged us to be bold in our requests. He knew we had very little power, so he taught us “collective begging with finesse.”

Worden said,“I was eager to return to Reese to share what I had learned. A couple of senior teachers were sent to the Superintendent’s office and inquired if we could have a copy of the Form B.” They were allowed only to copy its numbers, one at a time, by hand.

“The salary committee, chaired by the football coach, met a number of times. We then met with the Superintendent and pleaded our case for a two or three hundred raise and a step increase.

“A few days before school let out in June, the Superintendent called a faculty meeting and gave us the news of the Board’s salary decision. There would be a $100 dollar raise along with a step increase.”

Before bargaining was legal, low pay rates forced many teachers to work several jobs to make ends meet. Jim Matteson taught in Waterford Township schools in 1961.

“I worked summers at various jobs including the GM assembly line, painting houses, working in a dairy and being a rent-a-cop for a security firm.”

Ward worked summer jobs too. “Each faculty member had the option of spreading salary over 20 or 26 pay periods. The 26-pay option made my paycheck too small and my family couldn’t make it, so I took 20 pays which meant that each summer I had to find a job driving a truck, painting houses or working as a farm laborer.”

After PERA became law, real negotiations took place. Bob Buchner taught in Alpena and remembers this time well, “In Alpena, the two sides met in an historic new setting, groping their way into equal-power negotiations. Concepts never dreamed of emerged: grievance procedure; a set salary schedule; a mutually-determined calendar; insurance benefits; extra pay for extra work; paid personal days; accumulated sick leave; restrictions on extra assignments and association and board rights.”

“Thus began a new professional life for the Alpena Education Association teaching staff: no more unpaid assignments; no more arbitrary or capricious administrative action; and no more extra pay based on gender or board preference. Instead, the sides had a contract to implement, and for the Association, the most significant tool was the grievance procedure. Teachers experienced a new respect and dignity.”

“Thus began a new professional life for the Alpena Education Association teaching staff: no more unpaid assignments; no more arbitrary or capricious administrative action; and no more extra pay based on gender or board preference. Instead, the sides had a contract to implement, and for the Association, the most significant tool was the grievance procedure. Teachers experienced a new respect and dignity.”

Rood helped bargain minimum salaries and a salary schedule, both firsts for her school district. Grade school teachers were no longer paid less than high school teachers. Kemppainen and his fellow teachers now “had the right to negotiate salary, fringe benefits and working conditions without fear of being fired arbitrarily.”

These accomplishments are not carved in stone. With the loss of agency shop with the passage of Right to Work, school employees can now refuse to pay union dues, believing they don’t need a union. The reality of working in nonunion charter schools is employees fear retribution and are afraid to speak up about humiliating treatment. In Wisconsin, where collective bargaining rights were repealed in 2011, every aspect of employee work life is established unilaterally by the school boards in employee handbooks.

Supporting your union ensures you have someone by your side, keeps the many benefits of a collective bargaining agreement in place and gives you a strong voice in Lansing whenever collective bargaining rights are put up for a vote. Those who refuse to support their union put all this at risk.

Why You Need a Strong Union: The Wisconsin Experience

With the loss of almost all public school bargaining rights in Wisconsin, union influence has been vastly reduced. And as a result, working in the state’s schools has changed radically. Wisconsin school boards must negotiate “total base wages” only. Every other aspect of employee work lives is established unilaterally by the school boards.

Replacing bargaining is a process known as ‘Meet & Confer’. Just as it was in Michigan before the passage of the Public Employees Relations Act in 1965, Meet & Confer allows a meeting for employee input, but all decisions are made at the sole discretion of the school board.

There is no longer tenure or seniority rights and all school employees work at-will. Wisconsin school employees have no salary schedule; insurance, retirement and leave days are optional to each school board. School district contracts establish wages but are otherwise replaced by an Employee Handbook. Handbooks control work hours; contact, break and prep times; dress codes; required after-school activities and often impose controls on the personal lives of employees.

Grievances are possible for Handbook violations only. Appeals are often allowed, but only to an Independent Hearing Officer (IHO) hired by superintendent. The IHO findings are non-binding.

Strong unions preserve better classrooms, promote quality careers and secure retirements and support the best possible learning environment for children. A weaker MEA puts all this at risk.

School Employees As Fundraising Props

Because of continuing revenue problems, the nonunion charter school Arts and Technology Academy of Pontiac scheduled a May 2014 fundraiser billed as “Teacher Appreciation Week.”

To raise money, the administration emailed this notice to students and parents:

Parents were expected to come to school to put money in buckets held by the teachers. This humiliation was mandatory.

Staff were expected to dress in drag or hold a sign that read: “Save My Job.”Others would have pies thrown in the faces or have kindergarten students style their hair and apply makeup. And most incredibly, three teachers were expected to dress as babies.

Without a union, the school staff are powerless to resist these orders. They are “at-will employees” and can be terminated without cause. So they keep quiet and do what they are told.

Nonunion schools depend on a culture of fear where pleasing administrators is a crucial talent, one that is necessarily more important than teaching children.

At a school that has a union contract in place, with established working conditions backed up by grievance and arbitration procedures, such a fundraiser would be unthinkable.

It appears that today’s “”adult” leadership is adding to the ignorance of how to respect those trying to teach students academics as well as building character, responsibility, and respect for others. When I began teaching in 1961, unions were nonexistent, and men were pd more than women. By the time I retired, 2000, I worked in a union school district with representation and union support as needed. Let’s not move back to the 60″s.

Yes, I worked as a new teacher in Virginia. I am not the president of our local union and you betcha… things are different, better and the working conditions are more of a combined effort between the union and administration because there is an understanding.

I am now the president.